TIWI - THE BOOK

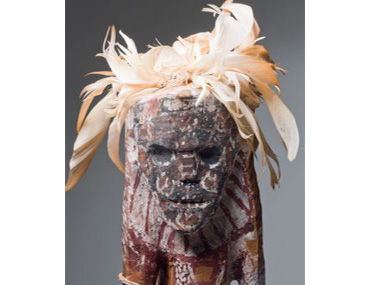

Detail from a 1963 scultpure by Enraeld Munkara - one of his 'Mourning Pukumani Figures' made at Paru

Jeremy Eccles | 19.12.12

Author: Jeremy Eccles

News source: Review

by Jennifer Isaacs, published by the wonderful Miegunyah Press at Melbourne University at $120

It's been an amazing year for Aboriginal art books – never known a better. If only I'd had time to read them all rather than just dip for in for the information and opinions that are useful to my writing!

It says a lot for the researches and persuasive capacities of the WA mob called FORM, but they managed to get a second door-stopper out of their important National Museum show on the Canning Stock Route. Ngurra Kuju Walyja – Stories from the Canning Stock Route is in some ways a reflection on the exhibition itself – but also contains academic asides like Jo McDonald's discussion of rock art on the CSR – which includes a pre-historic face that matches those on the Burrup Peninsular.

Also from the West and involving some of the same names – Tim Acker and John Carty – Ngaanyatjarra : Art of the Lands covers the contested art-making from Patjarr in the Gibson Desert to Maruku at Uluru – small, brave and shifting communities; Irrunytju thriving one minute and “just sitting and waiting for an art coordinator” the next. Look out for Minyma Kutjarra Artists in the future.

Involved in both books, the amazing Tjanpi Desert Weavers project got a book of its own, full of wonderful old women's faces and the popular creatures they construct out of desert grasses. The photography is a wonderful evocation of desert life.

And then, if you want to directly link the painters to their painting, Artists of the Western Desert, 2006/11 is your tome. Greg Weight has done his usual professional job on the portraits – all black and white – while the prolific Ken McGregor has chosen representative artworks – in colour, thank heavens.

Talking of prolix, the amazing Pat Corrigan has brought out a second door-stopper on an art collection that he only began in 2004! While he entrusted his thoughts to the McCullochs in the first volume, he's turned to Jane Raffan this time in Power + Colour; and there's no doubt that Pat likes them bright and beautiful, with some glorious Tommy Watsons, Jan Billycans, and an artist he's introduced me to, Akay Koo'oila from Aurukun.

If you want to think about Aboriginal art, but hardly need an image to light the way by, Ian McLean's academic compilation of others' essays – from Tony Tuckson in 1964 to Vernon Ah Kee in 2006 – in the challengingly entitled, How Aborigines Invented the Idea of Contemporary Art is as good as it's going to get.

And finally, we go to where it all started – in Arnhemland. The Kerry Stokes Collection of Larrikitj is by no means a self-referential publication by a rich man. It has the approval of 'The Man' in Yolgnu society – Gawirrin Gumana – and has complex thoughts about the essential links between Yolgnu art and life from Will Stubbs, Howard Morphy and Djambawa Marawili.

Christmas stockings will need to be replaced by pillow-cases!

And so to Tiwi – Art/History/Culture!

What a magnificent effort – the result of an all-to-rare feature of this strange business called Aboriginal art; continuity. Jennifer Isaacs has been involved with Tiwi life and creativity for 40 years; and it shows in her range of references, her depth of understanding and, occasionally, her partiality.

Having produced the still useful, if populist, Australia's Living Heritage in 1984, Isaacs has been sharing her understanding for a long time too. There are not many like her – far too many seek to act as door-keepers to 'The Knowledge'; others seek only to profit from their connections to it, however tenuous.

So, who are the Tiwi? A 2007 exhibition at the Art Gallery of SA translated the name of both the islands north of Darwin (we call them Bathurst and Melville) and their inhabitants as, “We the only people”. Isaacs doesn't go quite so far – though she does reveal that in the wonderful Tiwi mythology involving the man who invented death for them – Purukapali – he left the islands for Tipampunumi – the Land of the Dead, or the Australian mainland, 60 kms away! She also gives justified space to my old friend, Pedro Wonaeamirri to make a ringing statement of difference to mainland Aborigines. The 38-year-old also worries about the lack of interest in ceremony and the Old Tiwi language by a generation barely younger than himself.

A book like this could help him.

For there's constant linkage between the past and the present; and in the Tiwi world, Those links have often involved outsiders like Isaacs. She lists all the intruders into that world – from the Portuguese who tried to take slaves to the Brits who established Fort Dundas in 1824 as part of their efforts to deny a French or Dutch presence in New Holland – but were driven out in 1829. “Tiwi still wonder why the British came and stayed in a place that didn't belong to them”, she asserts, suggesting an untouched purity of world-view that's been comparatively corrupted on the mainland. It took a determined buffalo-hunter – Joe Cooper – with the help of some well-armed Arnhemlanders to come and stay. Interestingly, the Arnhem influence turns up later in the art.

Then came the Church, of course – and Father Gsell was smart enough to 'marry' any number of young Tiwi girls in order to hand them on to his nuns for an education! Many a good Christian name survives today.

But so does a culture and an artistic ethos that depends upon the Purukapali mythology to deliver a creation story based on human figures in a way that no other Aboriginal tribe in Australia does, as far as I know. And human ancestors naturally lead on to significant statuary – a key element in Tiwi art. Mind you, long-term anthropologist of Tiwi culture, Jane Goodale, who first visited on the Geographical Society 'expedition' of 1954 under Charles Mountford, did once tell me that Mountford was “a meddler who persuaded the Tiwi to paint stories on bark, when story-telling had had no place in Tiwi art before”. I'm quite happy that he did!

It's not a conclusion drawn from the several versions of the story in the book – both black and white - but I see the Purukapali story as one of those wonderful pieces of evidence that Aboriginal mythology still recalls the Matriarchy, and is honest enough to report its demise. So, at first there was Murtankala, the Earth Mother who arrived with three children in a tunga/basket – a universal signifier of woman the provider. She ordered a female sun to rise and shed light on the world (carrying ochre to cause red clouds at sunrise and sunset). Then she departed – allowing Purukapali to take centre stage, find a wife and have a son, and then reveal the weakness of women. For his brother took advantage of the lovely Bima, taking such a long time that the son who might have been future of the Tiwi world died of sun-stroke. Brother Tapara offered to bring him back to life; but Purukapali fought him instead (sending his battered face up to become that of the moon), and declared that death would now be the norm, carrying his son above his head into the sea.

He also decreed the appropriate Pukumani ceremony for them both; and the Pukumani poles that were collected by Stuart Scougall and Tony Tuckson for the AGNSW – the first Australian acceptance of Aboriginal art as art – are the result. Jennifer Isaacs also suggests that, “the aggressive painting and total abstraction” of Tiwi art consequently emerged in Tuckson's own work.

Thereafter, the nexus between Tiwi art makers and art collectors is at the core of the book – especially the fascinating revelation that the major collector and trader, Dorothy Bennett only discovered Aboriginal art as Dr Scougall's secretary! And it would seem that we may have her to thank for Isaacs' favourite artist - the little known Cardo Kerinauia. From the start, the author promotes the, “fiercely independent Kerinauia family at Paru” - just outside the Mission's control. Later, Cardo is hailed as “Tiwi's most dynamic carver”. You wouldn't know this if you cross-reference to Kathy Barnes's ATSIC-sponsored Good Craftsmen and Tiwi Art, which lists Cardo without suggesting he was bought by any Australian institution. The usually-reliable Bonhams auction house manages to mis-attribute a rare appearance of his work. But I bow to Isaacs' superior knowledge – though wonder whether she spent quite as much time at Milikapiti, the rival art centre to Paru - and wish there were more convincing pieces by Cardo shown in her book. For instance, there's an extraordinary unpainted work that has a medieval European craftsman's simple beauty about it, which appears in Lance Bennett's Japanese volume accompanying a tour of his mother's Collection to Japan. It was later bought by the National Museum.

A joy in Tiwi is Jenny Isaacs' willingness to slip in a politically incorrect googly. Early on she damns the Federal Government's Intervention as, “bad for staunchly isolationist communities like the Tiwi, with a culture based on land”. Sadly, the Tiwi seem to have been conned by no less a man than Mal Brough, who attended a meeting at which no local dared to ask any questions, allowing him to introduce the privatisation of community land. “We living in future now”, Isaacs reports a long-faced Tiwi as telling her.

And that future includes a disastrous attempt at forestry in which the good ol' commercial side of things was managed first by Great Southern Plantations (bust) and then by Gunn's (in receivership). What's worse, the advent of plantations has disrupted the passing on of lore and hunting skills to a new generation.

And then there's the shocking admission that once they'd been discovered by the AGNSW, “Tiwi artists saw an opportunity to also gain income from outsiders”. Of course, their prime motive was cultural. But the gate-keepers don't like you to mention money!

I've learnt so much – and still have questions. That's got to be a good thing. I don't yet have an insight into the symbolism behind significant coral paintings that appear in the book. And I understand that Pukumani Poles are created to signify a person's life – his/her character and achievements. So how can you create such a pole for an art gallery or white collector? And finally, I'd just love to know more about the unexplained (and inexplicable?) 1911 photo by Baldwin Spencer of an impassioned, solo Buffalo Dance in which the a couple of surrounding chorus men appear to be holding each other's penises. Or were my eyes deceiving me?

Great news – I've now done some research and find that Spencer himself solves my problem with his 1911 description of the event he was photographing: “The audience stood around in a circle, each man savagely stamping the ground with his foot, while in unison, they all struck their buttocks with their open palms, producing an extraordinary volume of sound that could be heard far away”. This surely explains those wandering hands!

URL + to Purchase: www.mup.com.au

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

'Kayimwagakimi Jilimara', a recent NATSIA Award-winning bark by Raelene Kerinauia, one of a younger generation of Tiwi artists reinventing the future.

That mysterious Tiwi Buffalo Dance, photographed by Baldwin Spencer in 1911!

Further Research

Artists: Cardo Kerinauia | Enraeld Munkara | Pedro Wonaeamirri | Raelene Kerinauia

News Tags: Baldwin Spencer | Charles Mountford | Dorothy Bennett | Jennifer Isaacs | Miegunyah Press | Pukumani Poles | Tiwi

News Archive

- 11.10.17 | RETURN OF MUNGO MAN

- 10.10.17 | TARNANTHI 2017

- 11.08.17 | Natsiaas 2017

- 08.08.17 | ABORIGINAL ART ECONOMICS

- 02.08.17 | SCHOLL'S NEXT MOVE

- 20.07.17 | APY ART DOMINATES THE WYNNE

- 17.07.17 | Anangu Artist Wins $100,000 Prize

- 14.07.17 | The End of AAMU

- 13.07.17 | YOU ARE HERE

- 11.07.17 | ART ACROSS THE COUNTRY

- 11.07.17 | TARNANTHI IN OCTOBER

- 05.07.17 | TJUNGUṈUTJA - from having come together

- 02.07.17 | BENNELONG

- 27.06.17 | JIMMY CHI

- 23.06.17 | Blak Markets at Barangaroo

Advertising