ABORIGINAL ART ECONOMICS

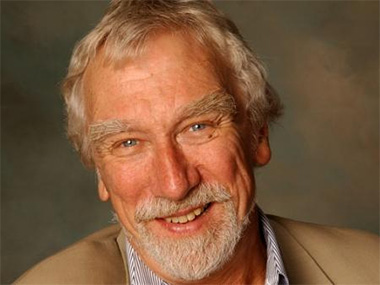

Prof. David Throsby, economist of the arts at Macquarie University

Jeremy Eccles | 08.08.17

Author: Jeremy Eccles

News source: Research

At a time when the whole future of the Indigenous relationship with non-Indigenous Australia is up for discussions like last night's eloquent ABC TV 'Q&A' program, the centrality of art-making to both the cultural and economic life of remote communities needs to be emphasised. And it emerges that two different bodies have been researching the matter and coming to significant conclusions.

But little has made it into the public eye.

Take a look at this conclusion by Macquarie University's pre-eminent arts economist, Prof David Throsby:

“Indeed it can be suggested that in a number of such locations, the only feasible pathway towards long-term economic and cultural sustainability lies in the production and marketing of artistic and cultural goods and services, such as visual and performing arts production, cultural tourism, cultural and environmental management and so on”.

Throsby, with fellow academic Ekaterina Petetskaya, has so far produced reports based on surveying individual artists in East Arnhemland and The Kimberley – about a hundred in each – which reveal the extent of their engagement with cultural matters going well beyond the visual arts, how little they earn from it, but how important it is to them.

And, in the light of that, it's important to demythologise the size of the art industry as it's been portrayed ever since the Senate Report in 2007 tossed about that notorious $200m. a year figure, which made us all feel so good. Now, the recently terminated Ninti One research organisation (aka the Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation) has gone over the books at 90 art centres over four or five years to conclude that, at the business end where artists are getting paid, Aboriginal art is but a $30m. a year business, with just $18m. going back to the artists and the rest helping to fund the art centres. Of course, they're all part of a bigger supply chain, including auction and secondary sales, but those don't benefit the artists at all in a financial sense.

With 14,000 artists working over the 10 years that were researched, Ninti One reckons that less than 3% of artists actually receive a living wage. “The vast majority are casual hobbyists, for whom the work is culturally important, and their contribution to the community economy matters more than their personal bank balance”, explained Tim Acker, Research Leader at Ninti One. “But only 8 to 10 of the art centres can claim to have a backbone of stability and continuity – the rest have a fragile existence, and it's really important to reduce that fragility, especially in their staffing. There needs to be a much better recruitment system for art coordinators, including more local employment”.

Further complicating matters is the fact that art centres are increasingly being asked to act as government service providers — implementing measures under the Closing The Gap and Stronger Futures policy imperatives of successive Commonwealth governments.

With Macquarie University's ongoing work, its “overarching purpose is to investigate and analyse the extent to which art and cultural production that has market potential can provide a viable pathway towards economic empowerment for Aboriginal people living in remote towns, settlements and outstations”. That last word is important because, not so long ago, Tony Abbott, the WA government and others were arguing that outstations were economically unviable and ought to be closed down. Hopefully, with “a nationally representative database on how individual Indigenous artists in remote Australia establish, maintain and develop their professional art practice”, the academics will be able to prove that the “Production of art and cultural services has the potential to make a significantly more substantial contribution to the economic sustainability of Aboriginal communities in remote Australia than it does at present, and it can do so in a way that links economic and business development with the maintenance of Indigenous culture”.

What Throsby and Petetskaya have discovered so far is that it's such a different world from the one Throsby is famous for – the art economics of non-Indigenous Australia, which he's been analysing since the 1980s. While they can cast doubt on Ninti One's claim that “only 10% of them actually received a living wage”, with the suggestion in Arnhemland that art is the main income for 30% of artists (a definition that includes music and dance performers, storytellers and writers, cultural board members (with a high 34% participation rate), film/media workers, and carers for Country), but like Ninti One, they had to go to the art centres to find details of artists' actual income. For the artists themselves were barely aware of numbers that, in The Kimberley, averaged out at only $12,200 for visual artists and $23,000 for performers. With welfare and other sources, the average total is $27,800. Incidentally, those numbers compared with a $40,000 average income for non-Indigenous artists and $14,700 for non-artist Aborigines in The Kimberley.

But then art isn't distinguished from ordinary life as it is in the cities. 90% of the Kimberley survey said they'd been involved in art for “all or most of their lives”, and 70% were currently practising. 98% had learnt from their family rather than an art school, and in Arnhemland, 93% had participated in ceremony, that fulcrum of the culture – though just 4% said they'd earned anything as a result. A much better ratio exists in cultural tourism – where 21% are involved and 19% paid; or in caring for Country – the burgeoning Ranger programs are helping there – where 68% participate and 33% are paid. And being 'on Country' is important for the making of art or making performance. Making medicines or cosmetics is also nice little earners.

Surprisingly, in East Arnhemland, one-third of artists have only started in the previous year – which suggests a continuing hunger for the market. And, indeed, 80% of Kimberley artists are unsatisfied by the amount of work they can do – seeing overseas and capital city opportunities as unmet currently. A full 90% see cultural activity as essential for their kids to get involved in, with economic potential too – though 70% in The Kimberley saw their art centres as too limited in capacity to support any more artists. 93% would be happy for the development of more cultural tourism in their remote homelands.

While Ninti One has finished its work, the Macquarie University surveys continue nationally.

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

Tim Acker, inveterate activist in the Western Desert, Canning Stock Route show curator and Ninti One lead researcher

Further Research

News Tags: Aboriginal art centres | David Throsby | East Arnhemland | Ekaterina Petetskaya | Jeremy Eccles | Macquarie University | Ninti One | The Kimberley | Tim Acker

News Archive

- 11.10.17 | RETURN OF MUNGO MAN

- 10.10.17 | TARNANTHI 2017

- 11.08.17 | Natsiaas 2017

- 08.08.17 | ABORIGINAL ART ECONOMICS

- 02.08.17 | SCHOLL'S NEXT MOVE

- 20.07.17 | APY ART DOMINATES THE WYNNE

- 17.07.17 | Anangu Artist Wins $100,000 Prize

- 14.07.17 | The End of AAMU

- 13.07.17 | YOU ARE HERE

- 11.07.17 | ART ACROSS THE COUNTRY

- 11.07.17 | TARNANTHI IN OCTOBER

- 05.07.17 | TJUNGUṈUTJA - from having come together

- 02.07.17 | BENNELONG

- 27.06.17 | JIMMY CHI

- 23.06.17 | Blak Markets at Barangaroo

Advertising