CRAP CRITICISM IN LONDON

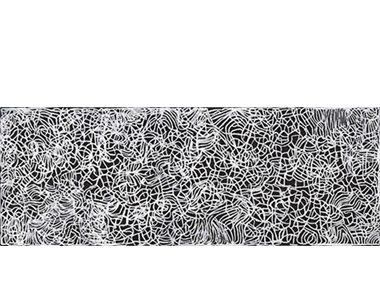

Emily Kngwarreye's 'Anwerlarr Anganenty' (Big Yam Dreaming) painting - 8 metres in width

Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 01.10.13

Dates:

21.09.13

: 08.12.13

Location: Royal Academy, Piccadilly, London W1.

The wilful ignorance of some London critics in slaughtering the Royal Academy's 'Australia' show of more than 200 artworks linked to our landscape is a deep embarrassment for the Mother Country. I've been a professional critic for many years, working across the arts of performance, the visual arts and Indigenous culture, and have edited papers on theatre criticism. But I'd never have dared to head into a performance or exhibition as ignorant and as opinionated as either Brian Sewell of the Daily Mail or Waldemar Januszczak of the Sunday Times. Worryingly, Januszczak has twice won critic of the year in Britain for such colourful phraseology as “John Olsen's Sydney Sun (mounted above the heads of viewers) successfully evokes the sensation of standing under a cascade of diarrhoea”.

Now I'm only really interested in the Indigenous content of the show – about 20% came from remote Australia and 6% more from the cities. Interestingly, no one that I've read has bothered his or her head (positively or negatively) with the urban/Blak art. And I still don't know all that is there in those elegant galleries off Piccadilly in London's heart. No list of artworks has yet been published, and the long-promised catalogue must be coming by sea from Britain! For I had talked to the RA curator (and Head of Exhibitions) Kathleen Soriano when visiting London in June, and came away with the impression that most of the work had been personally selected by her, though the National Gallery's Director Ron Radford and Head of Australian Art Anne Gray had both advised and argued the toss.

Subsequently, there's been the suggestion that Radford had been much more influential than this – pushing the claims of many works that he'd been involved in obtaining for either the SA Gallery or the NGA. One oddity, indeed, had been bought for the NGA but was later withdrawn from the RA when the artist declared it a fake! The catalogue might clear some of this confusion up.

Certainly, the RA had made efforts to prepare audiences for the Aboriginal art. Sculptor Anthony Gormley was recruited to help: “The works of the Indigenous Australians like those of Rover Thomas and Emily Kame Kngwarreye show the land speaking in the dream mapping of its original inhabitants. While artists from a deracinated European tradition continue to make pictures, the native Australian maps the experience of being the land and allows it to move through him or her. There is a directness in the Indigenous traditions, whether the dots of the Western Desert or the colour field paintings of the Great Sandy Desert, where pigment is used to carry mineral truth as well as lived feeling”.

Despite which Brian Sewell in the Daily Mail allowed himself to pontificate: “The exhibition is divided into five sections, of which the first is Aboriginal Art — but of the present, not the distant past, at last “recognised as art, not artefact”. By whom, I wonder? For these examples of contemporary aboriginal work are so obviously the stale rejiggings of a half-remembered heritage wrecked by the European alcohol, religion and servitude that have rendered purposeless all relics of their ancient and mysterious past. Swamped by Western influences, corrupted by a commercial art market as exploitative as any in Europe and America, all energy, purpose and authenticity lost, the modern Aboriginal Australian is not to be blamed for taking advantage of the white man now with imitative decoration and the souvenir. The black exploits the white’s obsession with conspicuous display and plays on the corporate guilt that he has now been taught to feel for the ethnic cleansing of the 19th century — a small revenge for the devastation of his culture — but the Aborigine offers only a reinvented past, his adoption of “whitefella” materials and, occasionally, “whitefella” ideas (Jackson Pollock must surely lie behind the longest of these canvases) undoing his “blackfella” integrity”.

The extraordinary thing was that Sewell started his piece with some of the most politically correct coverage of Black/White relations in Australia, and he clearly thinks he's a 'goodie' – using such 'cool' terms as blackfella and whitefella. But his patronising assumptions about the realities of Black Australia – alcohol, religion, servitude causing the destruction of a culture (“the stale rejiggings of a half-remembered heritage”!); and the disgusting assumption that Emily Kngwarreye could only have produced her Yam Dreamings after seeing the dribblings of Jackson Pollock are matched by his denial of the possibility of artistic responsibility in Indigenous artists in his throw-away: “at last “recognised as art, not artefact”. By whom, I wonder?”.

Gee, it's almost as though he's been reading and believing Richard Bell's insulting 'Bell's Theorem' with its attempt to prove that the Ooga Boogas of remote Australia are only making work for tourists, while 'The Dreaming' had passed to him in Brisbane! Or could he have heard Vernon Ah Kee complaining that he wasn't seen as “primitive enough”, burdened as he was by the popularity of the “art of Stone-Age Aborigines”.

The fact is that an artist like Kngwarreye painted her significant yam-root heritage as soon as she picked up a paint-brush without any hint in her remote Simpson Desert life that Abstract Expressionism might have existed. The roots to her were not just dribblings, but spoke of many other things - community harmony, the umbilical links between mother and off-spring, the health of a society wracked by diabetes, and of seasonal fertility. Her 'art' was not just about art but spoke of her knowledge of and concerns for her Anmatyerre society, given visual form using the mnemonic patterns inculcated over centuries of survival in harsh conditions. And, as she mutated her story-telling/painting style year by year, Aussie expat and Time art critic Robert Hughes 'recognised' the burgeoning Aboriginal cultural flowering as “The last great art movement of the 20th Century”.

And then we move on to the once-great Sunday Times, where Waldemar Januszczak complained that the Indigenous element of the survey was tokenistic, preferring original ancient rock art to the “dull canvas approximations, knocked out in reduced dimensions, by a host of repetitive Aborigine artists making a buck. Out of a tremendous Indigenous tradition, fired and inspired by an enormous natural landscape, the Australian art world has managed to create what amounts to a market in decorative rugs. Opening the show with a selection of these spotty meanderings, and discussing them in dramatically hallowed terms, cannot disguise the fact that the great art of the Aborigines has been turned into tourist tat".

I guess Andy Warhol and David Hockney never thought of “making a buck”! Or Albert Namatjira – whom Waldemar liked rather a lot!

Januszczak clearly has no idea how the Desert art movement developed from an active tradition of painting on bodies, on sacred artefacts and ground painting. And the idea that rock art is authentic but anything created to be portable and marketable can't be simply reveals the limited thinking of a 19th Century ethnographer rather than an art critic. The Empire lives on! One can imagine Januszczak coming out here to organise a really superior system of assimilation or to establish awfully nice Homes for half-caste children in the name of such a superior civilisation.

Fortunately, not all Brit-pack critics live in such ignorant bliss in ivory towers. The FT's Jackie Wullschlager seems to have researched her way through the mysteries of Indigenous art and culture quite successfully: “In 1971, Geoffrey Bardon, a teacher living among Aboriginal people in Papunya in Australia’s Western Desert, invited senior men from the community to create murals on his school walls in the style of their own traditions. Accustomed to painting their bodies and ceremonial objects, the men went on to use acrylics and ochre on sections of board, adapting with flair to the new materials, and producing works that were fresh, visually arresting and captured the moment.

“These paintings, which open the Royal Academy’s Australia exhibition, form the continent’s only original art movement. To Western eyes, the overlapping concentric red circles of Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra’s “Kalipinypa Water Dreaming”, the patterns of coloured dots and feathery white cross-hatching in Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula’s “A Bush Tucker Story”, and the shimmering pink/purple ridges of Timmy Payungka Tjapangati’s “Sacred Sandhills” look like bold abstract compositions. Painted in 1972, all show extraordinary affinities with contemporary 1970s western art – the elegant austerity of minimalism, innovations of land and body art, influences of identity politics, anthropology, environmentalism.

“None of this was in the minds of the Aboriginal painters, displaced from their homelands and encountering white people for the first time. Their images belong to Dreaming stories – creation narratives indissolubly connected to land and place, passed down through patrilineal lines. In this iconography, Tjakamarra’s circles represent rain or water dreamings; beneath the dots and dashes of “A Bush Tucker Story” lie graphic symbols denoting sacred sites and pathways.

“Such symbols go back 40,000 years. The fingertip dotting replicates the ancient processes of placing clusters of ochre on the ground; animated stippled surfaces, like those of “Sacred Sandhills”, express the presence of ancestral forces in the land. Thus a new genre developed in unbroken tradition from the world’s oldest art movement.

“The early examples here have an innocence, a thrill at new-found virtuosity that could not last. Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri’s “Warlugulong” (1977) is already more sophisticated, depicting nine dreamings, beginning with the bushfire created by Lungkata, the Blue-tongued Lizard Man, to engulf his ungrateful sons. Executed on canvas, “Warlugulong” integrates the sacred diagrams of ground painting with European mapping conventions to suggest an aerial view of a rich, dense landscape.

“As the Desert painting movement spread, Aboriginal communities grew wary about making sacred Dreamings public. In 1974 elders in Kimberley interpreted Cyclone Tracy as a sign from an ancestral Rainbow Serpent warning that European interest was destabilising traditional culture. Employing a radically simplified dotted style in natural earth pigments, Rover Thomas in “Cyclone Tracy” and “Roads Meeting” – where an ancestral red dirt track crosses a modern bitumen road – traces landscape as violent history, scarred by those who traverse it.

“The largest Aboriginal work here is an eight-metre canvas of livid tangled white skeins of paint, “Anwerlarr Anganenty (Big Yam Dreaming)”, by Emily Kame Kngwarreye. How authentic is it? A ceremonial leader who began painting on canvas in her seventies, Kngwarreye was promoted as an overnight sensation and became the first Aboriginal artist to sell for more than $1m. Her vigorous all-over compositions recall Jackson Pollock – perhaps too closely. One example is not definitive but, according to Philip Batty, senior curator at Melbourne’s Victoria Museum, Kngwarreye’s later work is simply “a mirror image of European desires”.

“This is where Aboriginal art meets non-indigenous Australian painting.”

A comforting conclusion, perhaps – but maybe Wulschlager should check out the earliest of Emily's works, done before she'd made it into Alice Springs let alone Canberra. There, her subterranean yam roots may lack the boldness of the black on white Big Yam Dreaming, but they owed nothing to bloody Pollock!

There's less equivocation in The Independent, where one Adrian Hamilton has some good thoughts: “There is no doubt an element of penance in the way that Australia has elevated Aboriginal art in the last twenty years. The treatment by the settlers of the indigenous population has been truly horrendous, including enforced castration, bounty hunting and enforced separation of children from parents. It was not until 1967 that a referendum allowed them citizenship as of right. The attempt to make up for past sins by ennobling their culture has led to some spectacular frauds, in which false art has been sold as true native expression to a gullible public. Nor can you divorce professional tutelage and art gallery taste from works produced for a Western market. The search for the “authentic” in native art is always a perilous business.

“The RA rightly brushes all this aside in a glorious opening gallery, where the visitor is faced with a series of earth-coloured, snake-weaved and rhythmic works by contemporary native artists of quite extraordinary breadth and freedom. Painting in the form of rock art, body decoration and ceremonial composition in the sand have always been an integral part of the Aboriginal culture – a means of expressing the oneness of community, with nature, future and past which lies at the centre of their belief and their “dreaming”. The meaning of the circles, lines and dots may be obscure to the Western viewer, but not the overall effect of swirling shapes and ochre backgrounds in works by John Mawurndjul, Emily Kame Kngwarreye and the group effort of the Martumli Community’s Ngayarta Kujarra.

“The special bond between place and people forms the theme of the RA’s show.

“If the show ends on an incomplete note, it is because its art, like the country at large, seems still uncertain of where it is going. For all its size, Australia is still a nation of only some 22 million people – barely more than a third of the United Kingdom’s. No wonder it puts so much emphasis on its native Aboriginal artists. They at least seem confident in their dreaming“.

How splendid that Mr Hamilton has the courage to distinguish between the confidence levels in Indigenous and non-Indigenous art – which few art critics at home would dare to do. But then perhaps he was feeling the need to apologise for the efforts of his predecessor Tom Lubbock when reviewing the all-Indigenous show, Aratjara in 1993: “I don't very much like these works. I don't very much dislike them either. To be honest, I find them a bit boring - which is the most difficult kind of response to articulate properly. But panning the mind superficially over all the art I've ever seen, it strikes me that the art represented in Aratjara is perhaps the most boring art in the world. Well, something has to be”!

Is all this angst justified in provoking debate about the position of Indigenous art within the Australian context? It's not a debate we have here too often.

But it has provoked some intense Commentary in the tail to on-line articles. I have to say my favourite came from an outraged Aussie in The Guardian: “Perhaps the Brits can go down to the Saatchi Gallery and gaze lovingly at the cum-stains on Tracy Emin's bedsheets for some real culture, eh?"

And, talking of The Guardian, its Australian site recently commissioned a dozen local writers to nominate their favourite artwork – and justify it. One third, interestingly, chose Indigenous art – the same proportion as the RA show. And the excellent Alex Miller chose Emily's Big Yam. His brief thoughts are clear and courageous: “Indigenous Australian art is the first source of imaginative energy that derives immediately from Australia and nowhere else to challenge art in general”.

URL: Royal Academy

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

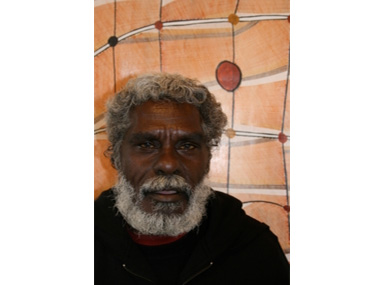

Maningrida's John Mawurndjul in front of one of his 'Mardayin Ceremony' barks

Further Research

Artists: Albert Namatjira | Clifford Possum | Emily Kngwarreye | John Mawurndjul | Johnny Warangkula | Long Jack Phillipus | Rover Thomas | Timmy Payungka

News Tags: Adrian Hamilton | Anthony Gormley | Brian Sewell | Jackie Wullschlager | Jeremy Eccles | Royal Academy | Waldemar Januszczak

News Categories: Europe | Event | Exhibition | Feature | Industry | Media | News

Exhibition Archive

- 02.06.20 | RIP Malu Gurruwiwi – Custodian of the Banumbirr

- 11.05.20 | BIDYADANGA CLOSE-UP

- 07.05.20 | Boomerang Back to the Start

- 29.04.20 | Cooked???

- 24.04.20 | Mrs Ngallametta

- 23.04.20 | NATSIAA Pre-Selections Revealed

- 20.04.20 | CIAF 2020

- 10.04.20 | Marginally Good News

- 06.04.20 | ON & OFF IN ABORIGINAL ART

- 26.03.20 | Out on Country!

- 19.03.20 | BIENNALE OF SYDNEY 2020

- 13.03.20 | LAURIE NILSEN

- 03.03.20 | EMILY v CLIFFORD

- 02.03.20 | The Ephemeral and the Ineradicable

- 25.02.20 | WADJUK IN THE BLACK

Advertising