BIENNALE OF SYDNEY 2020

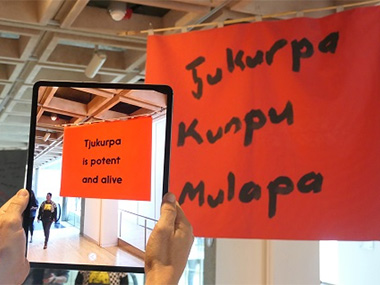

Banners in tribute to Kunmanara Mumu Mike Williams in the foyer of the Art Gallery of NSW, with digital translations

Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 19.03.20

Dates:

13.03.20

: 08.06.20

Biennales come and go and are often remarkably forgettable. Every second artist – whatever their cultural roots – seems to live in Berlin. The sort of globalisation that has brought us the coronavirus invariably flavours each show – art passed from hand to mouth across a hundred countries, all ending up Unter der Linden.

So a welcome to Brook Andrew's 2020 effort which has so much more cultural specificity. With a Wiradjuri mother and identifying strongly Indigenous, Andrew has not simply trawled the world for fellow First Nations artists. But he has made a powerful point that his vast exhibition of 101 artists at eight different venues stretching from Campbelltown to the Art Gallery of NSW via Cockatoo Island and the Parramatta Female Factory is a “safe place” for artists of colour, divergent sexuality and possibly enforced diaspora.

I don't think he intends that to mean that the art is safe. For this is a man whose own art over 20 years has invariably been provocative, from his 2002 artwork, 'Sexy and Dangerous' on. Significantly, as far as his Biennale is concerned, many of his own artwork designs have been based on Wiradjuri dendroglyphs – the sacred patterns cut deep into tree barks across NSW. And the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) contains not only historic film of these trees being destroyed but a mould of one such trunk taken off to a museum in Oxford where Andrew is currently researching for his DPhil. Andrew has also made a frequent point of disrupting art galleries' displays of colonial art with his own. Now he's imported Madagascan, Haitian and Spanish artists to do the job for him in the august Old Courts of the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW).

Finally, in what might be thought of as a trial run for this Biennale, back in 2012 Andrew curated the provocative show, 'Taboo' at the MCA with many of the same league of marginalised artists as turn up in Sydney today. He also essayed the use of the vitrine in which to place 'Powerful Objects' as he calls them at a number of BOS venues – not contemporary material but offering challenging context to the new art around them. As Andrew puts it: “These are resilient pieces of evidence, modes of storytelling, clues and traces, all reminding us of forgotten or ignored ceremonies, histories and trajectories set forth by communities, artists … silent witnesses and healers – some un-named or un-recorded”.

So the curator can't deny his existence as an artist.

And his Indigeneity naturally results in his selection of artists predominantly from First Nations backgrounds – with first-time representations from countries such as Nepal, Georgia, Afghanistan, Sudan and Ecuador. But there are also 39 Australian artists or artist groups, almost 40% of the total, a high percentage by the proudly international BOS standards.

Let's talk about them first – for I must admit to being a bit blinkered when I'm asked to understand Australian Aboriginal (no Torres Strait Islander) art beside Haitian and Madagascan.

You can't miss it, though at the AGNSW. The entrance foyer offers a field of Karla Dickens's disturbingly imprisoned sculptures, but that leads in to a bannered hall where the famous imagery created by the late Pitjanjatjarra artist (and author) Mumu Mike Williams has been taken on by his family and his community in his memory. In a development from his practice of abusing colonial Australia for stealing his land in his own language, you can hold a device up to each banner to obtain a salient translation. (see pic). Williams, the great communicator would be proud.

Heading left from there – all the BOS works are on this ground floor – the Mulka Centre at Yirrkala in eastern Arnhemland has also gone in for some community technological development. Their 'Watami Manikay' brings together a group of their most adventurous artists in a darkened room to surround you immersively with the beauties of Yolngu Country, the sounds that encapsulate it for them, and a mighty larrakitj upon which a variety of ceremonial minytji patterns are overlaid digitally. They don't stand still at the Mulka! I've seen 's mullet progressively rise from bark to poles to the digital world at the NATSIAAs over many years, and at last year's Tarnanthi – though he never loses the foundation gunda – the rock that grounds each clan to its identity.

Other artists involved are young film-makers Patrina Mununggurr and Ishmael Marika, freshwater woman Mundatjnu Mununggurr and the deaf saltwater man, Gutingarra Yunupingu who brings Baru the sacred crocodile into the picture.

Photographer and recorder of Blak urban life, Barbara McGrady has still imagery at the AGNSW, but her real strength shows at the Campbelltown Art Centre where a huge darkened room is filled with a more performative version of those images – funerals, footy, protests, etc – given provocative captions and set to unhelpful music that gives the impression of an entertainment. It's fascinating to compare with John Miller and Elisapeta Heta's quiet stills of Maori life and protest in Aotearoa/NZ. I wonder which is more effective politically?

At the Powerhouse Museum, Dion Beasley from Tennant Creek shows his 'Cheeky Dogs' and, as I noted when Salon Projects took him to the Perth Festival, he “has added colour to his repertoire – but not much....in an extensive show of canine works from his home at Canteen Creek, which includes a map that might be seen as having a resemblance to Hundertwasser's Viennese art. Much fighting, a multi-story dog-wagon to extract unwanted strays and a work with no fewer than 38 hounds delight with their essential truthfulness and wit”.

Tennant Creek also gets many a guernsey at venues across the BOS in the intriguing form of a collective called Tennant Creek Brio. Artspace has a room full of repurposed poker machines, and Cockatoo Island has a tower of powerful images reaching up to the roof. No evidence of traditional culture, some hints of Egyptian icons, an Aboriginal elder smoking a pipe, and just a suggestion of 'Here be Dragons'. No idea what it means but it certainly has character. Turns out it was a social work project organised by Melburnian Rupert Betheras working with the men who'd felt universally condemned after the terrible child rape case in TC – and the results suggest a hefty, new-found determination.

Missing determination – surprisingly – was the work on Cockatoo by Warwick Thornton, maker of significant films such as 'Samson & Delilah', 'Sweet Country' and 'We Don't Need a Map'. His intention to upset the Ned Kelly mythology by filming him on drugs in the Inner West alleys of Sydney fell totally flat.

Falling a little less flat through repetition were the artists who Brook Andrew had decided to give multiple outings to. Even the great Nonggirrnga Marawili lost out for me by popping up all over the place with her now trademark barks and poles given a pink sheen from printer cartridges. And the Namatjira School of artists at Iltja Ntjarra in Alice Springs were literally everywhere – though almost invisible as they'd taken those ubiquitous Chinese plastic striped laundry bags and given them landscape on one side and a political cri de coeur on the other. Tony Albert is responsible for encouraging these gentle water-colourists to go opinionated with the likes of Macdonalds logos imposed on Mount Sonder, which just clash. I'm sure they have political views – I'm sure Albert Namatjira had them too – but do they sit comfortably with their traditional art?

Tony Albert pops up repeatedly too, most effectively in a native garden of reflection on Cockatoo Island. I think there are three gardens in this bucolic Biennale.

The Dharug-Dharawal artist Venessa Possum Starzynski, on the other hand, gets just the one chance to exhibit 'Ngurra Bayali' ('Country Speaks'), a series of large-scale textile rubbings made on Country at the former Blacktown Native Institution. Sadly unseen to date.

Outside Australia's First Nations creators, I was sucked into the Middle East with photography that captured the trauma of this favourite war zone of Western forces. Aziz Hazara at the MCA simply puts kids on a rock high over an unnamed town and places them surround-sound around you. One struggles to even get his lean body up on the rock in the face of a powerful wind. What determination! It's totally moving.

Meanwhile, Shaheed at Campbelltown photographs boys playing cricket with improvised equipment in a bomb-shattered street – the war erased momentarily from their young lives. What a wonderful contrast to Drysdale's rural cricketers at Hill End. Could Shaeed possibly have known of this fascinating point of comparison?

But what crazy contrasts in the Old Courts at the AGNSW. Bodies hanged on a vast scaffold, black curtains covering the art that plays a valid role in our history, Voodoo figures beside brave bronzes, and incomprehensible abstraction stuck up next to the classics of our imagination. It certainly made me appreciate the classics! And it reminded me that the Art Gallery had placed its 1959 Pukumani Poles collected by Tony Tuckson in the middle of the Old Courts in 2009 – inspiring a much more cogent response from me: “This challenging placement of Pukumani Poles (Tutini) and barks up against a work like John Glover's fictitious 'Natives on the Ouse River' has the ironic effect of reminding us that this bucolic idyll was in fact the artist's own protest against the clearance of Aborigines out of mainland Tasmania - “an Arcadia they'd fucked up by 1838”, as curator Barry Pearce brutally summed that painting up” at the time.

As far as I know, the BOS 2020 exhibitions are all open though tours, lectures and other gatherings are not happening. Do try it out, and bear in mind as you travel the words of the Maori artist Megan Tamati-Quennell, who spoke at an Indigenous curators symposium over the weekend: “This event brings together Indigenous people united by our tears that then run into the sea and join together”.

Can those tears join together online??? For (UPDATE) the Sydney Biennale has closed down physically as a result of government directives re the Coronavirus Pandemic.

But....."Working with long-time Biennale partner Google - and in a first for the Biennale of Sydney - audiences around the world will be able to engage with NIRIN on the Google Arts & Culture platform. Creating a virtual Biennale will bring the exhibition and programs to life through live content, virtual walk-throughs, podcasts, interactive Q&As, curated tours and artist takeovers".

URL: https://www.biennaleofsydney.art

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

Biennale of Sydney Director, Brook Andrew with BOS CEO Barb Moore in front of Inuit script at Artspace in Sydney

The most powerful image in BOS 2020 - Aziz Hazara's Afghan boy fighting the wind and his uncertain future

Further Research

Artists: Dion Beasley | Albert Namatjira | Barbara McGrady | Brook Andrew | Gutingarra Yunupingu | Ishmael Marika | Karla Dickens | Mumu Mike Williams | Nonggirrnga Marawili | Patrina Mununggurr | Tony Albert | Venessa Possum Starzynski | Warwick Thornton | Wukun Wanambi

News Tags: Art Gallery of NSW | Artspace | Barbara Moore | Biennale of Sydney | Campbelltown Art Centre | Cockatoo Island | Jeremy Eccles | Mulka Centre | Museum of Contemporary Art | Wiradjuri dendroglyphs

News Categories: Australia | Blog | Event | Exhibition | Feature | Festival | Industry | News

Exhibition Archive

- 06.04.20 | ON & OFF IN ABORIGINAL ART

- 26.03.20 | Out on Country!

- 19.03.20 | BIENNALE OF SYDNEY 2020

- 13.03.20 | LAURIE NILSEN

- 03.03.20 | EMILY v CLIFFORD

- 02.03.20 | The Ephemeral and the Ineradicable

- 25.02.20 | WADJUK IN THE BLACK

- 17.12.19 | Sotheby's NY Inaugural Aboriginal Art Auction

- 11.12.19 | Festivals in the Blak

- 11.12.19 | Cairns Airport Commission

- 09.12.19 | KNOWLEDGE GROUND

- 30.11.19 | Linear?

- 28.11.19 | The Auction Time of Year

- 25.10.19 | It's Time for Tarnanthi

- 02.10.19 | FIBRE ALCHEMY

Advertising