THE BRITS EXPERIENCE INDIGENOUS CIVILISATION

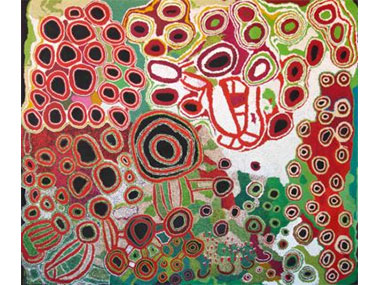

'Kungkarangkalpa' by Kunmanara Hogan, Tjaruwa Woods, Yarangka Thomas, Estelle Hogan, Ngalpingka Simms and Myrtle Pennington, (2013), Acrylic on canvas © The artists, courtesy Spinifex Arts Project

Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 23.04.15

Dates:

23.04.15

: 02.08.15

Location: British Museum, Fitzrovia, London

Oh, the Poms love to get in a tizz about Australian art and culture! Remember the 'Australia' show of landscapes 18 months ago at the Royal Academy – we were mocked left, right and centre for trying to reflect the world around us, and, in particular, for encouraging the poor Aborigines to imitate white Australia's failings with art that was “so obviously the stale rejiggings of a half-remembered heritage wrecked by the European alcohol, religion and servitude that have rendered purposeless all relics of their ancient and mysterious past”.

That was one Brian Sewell, 'art critic' of the Daily Mail.

And then there was Waldemar Januszczak, 'prize-winning critic' of the once great Sunday Times: “Out of a tremendous Indigenous tradition, fired and inspired by an enormous natural landscape, the Australian art world has managed to create what amounts to a market in decorative rugs”.

Well, they're at it again! Under attack now is the big, entirely Indigenous exhibition opening today at the British Museum with the very careful, un-Terra Nullius title, 'Enduring Civilisation'. But guess who's jumped on the good ship repudiation? One Zoe Pilger! Surely not the off-spring of the expat polemicist, John, whose 2014 film, 'Utopia' caused me to respond, “Pilger too fails to understand. His is an entirely superficial political view of Indigenous Australia without any cultural underpinning. And when he comes to the end of this looooong documentary, his thoroughly reasonable proposal for a treaty is justified on naïve Capitalist grounds that we should all “share this rich country, its land, resources and opportunities”?

Ms Pilger has seen one too many of Daddy's films. In The Independent newspaper, she opines: “Indeed, this exhibition is half in denial. It both acknowledges the violation of the indigenous people and censures that violation. (I think she means censors) It uses terrible metaphors: the histories of the indigenous people and the colonisers are "entangled", "interlinked", born of "encounters" and "misunderstandings". These words are ways of repressing the fact that white Australia is founded on murder”.

And she continues: “The inclusion of the memorial pole, 'Barama/Captain Cook at the Sacred Waterhole of Gangan' (circa 2002), should be viewed with suspicion. It is the work of Gawirrin Gumana of the Dhalwangu people in the northeastern Arnhem Land. One side of the pole is painted with the face of Barama, a creation ancestor who brought into being the laws of nature and society. On the other side is the face of Captain Cook. The symbolic coexistence of the laws of the Dreaming and those of the coloniser is presented as a vision of harmony and forgiveness. According to the wall text, the design is "a gesture of historical and political generosity." But why should the artist be generous?”.

Well if she knew anything about the remarkable Yolngu capacity for generosity in the face of white rapacity, she could not have asked such a question. Instead, Zoe oppresses them with a simplistic binary obsession with race and her assumption that Yolngu philosophy is as racist as her own. The saintly Gawirrin is being polite. But he is fully aware that Barama is a god; all powerful and creative. Cook is just an interloper who bumped into reality.

To be fair, the Poms have been encouraged in their negativity by the likes of Shane Mortimer, an elder of the Ngambri people from Canberra (where I've always thought the Ngunawal people lived): “If the Ngambri people went to England, killed 90% of the population and everything else that is indigenous to England and sent the crown jewels back to Ngambri Country as a prize exhibit … what would the remaining 10% of English people have to say about that?”.

And then there are the long-standing plaints of Gary Murray, who was central to a failed Dja Dja Wurrung attempt to have some 1850s barks from Western Victoria that had been sold to the British Museum returned to his people while they were on loan to the Melbourne Museum in 2004. Murray, supported by activist Gary Foley invoked the Federal Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act to seize the barks while they were in Victoria. After a protracted court case the barks were returned to London and the 2013 Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan Act was passed to ensure that such a problem shouldn't arise again – particularly when some of the BM's 6000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander works come to the National Museum in November.

Sadly, much that might have been available here was destroyed when the Australian Museum's significant ethnographic collection was largely destroyed when the Garden Palace in Sydney that was housing it burnt down in 1882. And contemporary artist, Jonathan Jones will attempt to recreate the feeling of that in a John Kaldor project over the next year.

What's so regrettable about this wave of negativity is that all parties involved – guided by the BM's Indigenous curator Gaye Sculthorpe from Tasmania (a distant relation of Peter, the late composer), a 13-year member of the National Native Title Tribunal, and therefore pretty political herself – have attempted to get contemporary Indigenous people engaged in the project over a number of years. The ‘Engaging Objects’ research side of it, undertaken jointly with the National Museum of Australia and the Australian National University, put people in touch with the Museums’ collections both in Australia and in London in order to engender critical and reflective discussions, new works of art, research and curation. Through such enthusiastic collaboration with Traditional Owners, the Indigenous collections have been reconsidered and researched, and new avenues of enquiry opened up for further mutual investigation in both countries.

When the objects go back to Canberra for exhibition, many Indigenous Australians will see them for the first time since they were collected in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. For some, this will raise issues about access to items of their cultural heritage. For others, the exhibition in London will be seen as an important moment to engage with an international audience about the place of Indigenous Australians in contemporary Australian society. That these museum objects continue to provoke topical debate, evoke wonder and engage with topics at the heart of Australian society is a testament to their enduring value.

It can hardly fail to be be more beneficial than the British Museum's last effort as recently as in 1973, when visitors were told about “extinct Tasmanians” and how “in many cases, tribal organisation has broken down (so) the assimilation of Aborigines into white Australian society is proceeding, but with varying degrees of success”!

Now, they can engaged with people like the North Queensland artist, Abe Muriata. As a child, he saw his grandmother making baskets from lawyer cane found in the rainforests, and as an adult began experimenting to make his own: ‘I used to watch my old grandmother make them, but I wasn’t actually taught by her. I taught myself by going to the museum and looking at the real... the old, the ancient artefact done by real master craftsmen. So I can say I’ve been taught by master craftsmen, rather than anything else”. Muriata is now one of Australia’s finest basket makers, represented in the collections of many museums.

And with Wiradjuri artist and curator, Jonathan Jones. He was invited to come up with a concept encase the exterior of the British Museum’s historic Reading Room with hundreds of fluorescent-light tubes. The notional artwork’s pattern echoes the engraved line designs found on Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi shields, clubs and boomerangs that are found in institutions such as the British Museum. Jones explained: “Traditionally, for ceremonies and performances, the engravings on these objects would be infilled with white ochre, and in this way the fluorescent tubes of the artwork trace the white ochre lines, remembering the hands of my ancestors. The layering of these designs on to the Reading Room comments on complex and entwined knowledge systems. Like words in books, these designs are encoded and layered with tradition, history and knowledge. They map country and community, speaking of ancestral actions and the energy these actions infused into the land”.

Two shields from the British Museum collection with particularly interesting stories will be shown. The first is the one acquired by Captain Cook in his first conflict with the locals at Botany Bay. It was assumed to have been made from eucalyptus, but recent research has revealed it to be red mangrove, which grew no closer than 500km to the north of Botany Bay - suggesting the existence of previously unknown Aboriginal trading links over such a vast distance. Another shield was made in Melbourne’s prison by Peter Mungett, an Aboriginal who in 1859 refused to testify in a rape case because he did not regard himself as a British citizen. His death sentence was consequently commuted to imprisonment.

Much, much more will emerge from 'Enduring Civilisation' over coming months, especially when the substantial catalogue is digested. But all involved must be pretty pleased with the first reaction of Jonathan Jones (British critic not Aussie artist) in The Guardian. “A fabulous beast” appeared in the headline – an odd description, one might suggest. But the review's emphasis on the exhibition's revelation of Indigenous civilisation was important in, what Jones admits was the absence of “Greek statues and classical music when Cook arrived” to completely ignore “a settled sophisticated way of life with a deep sense of history and place”. He also felt the story was “movingly told” and “thought provoking”.

“Should such sacred works be in the British Museum?”, Jones, however, queried. “Certainly they are enlightening in this show”, he responded, “and are not just an aesthetic fetish”. He also noted “revealing Aboriginal inventions that enabled the long-term settlement of lands without wrecking them. Who today can call that a primitive way of life? Here is wisdom the world needs to listen to”.

I wonder whether Messers Sewell and Januszczak will discover anything like that?

The National Museum of Australia in Canberra will later be showing a different version of the show, entitled “Encounters” (26 November-28 March 2016). That exhibition will include 85 contemporary objects in the Canberra collection, along with 150 loans from the British Museum.

URL: http://www.britishmuseum.org/whats_on/exhibitions/indigenous_australia.aspx

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

Mask from Mer in the Torres Strait made before 1855 and an inspiration to artists such as Alick Tipoti. Turtle shell, shell, fibre © The Trustees of the British Museum

Shell Necklace of the sort created by Lola Greeno today, displayed at the Great Exhibition, London, 1851. From Oyster Cove, Tasmania and made before 1851 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Further Research

Artists: Abe Muriata | Alick Tipoti | Estelle Hogan | Gawirrin Gumana | Jonathan Jones | Kunmanara Hogan | Lola Greeno | Myrtle Pennington | Ngalpingka Simms | Tjaruwa Woods | Yarangka Thomas

News Tags: Aboriginal artefacts | British Museum | Enduring Civilisation | Gaye Sculthorpe | Jeremy Eccles | National Museum | NMA | The Guardian | Zoe Pilger

News Categories: Australia | Blog | Europe | Exhibition | Feature | Industry | News | What's on?

Exhibition Archive

- 10.10.17 | TARNANTHI 2017

- 11.08.17 | Natsiaas 2017

- 20.07.17 | APY ART DOMINATES THE WYNNE

- 17.07.17 | Anangu Artist Wins $100,000 Prize

- 14.07.17 | The End of AAMU

- 11.07.17 | ART ACROSS THE COUNTRY

- 11.07.17 | TARNANTHI IN OCTOBER

- 05.07.17 | TJUNGUṈUTJA - from having come together

- 13.06.17 | Ghost-Nets Straddle the World

- 07.06.17 | Grayson Perry Going Indigenous?

- 05.06.17 | Barks Bigger than Ben Hur

- 27.05.17 | NGA QUINQUENNIAL 2017

- 21.05.17 | Blak Douglas Finds Home at the NGA

- 21.05.17 | BRIAN ROBINSON WINS HAZELHURST WOP

- 18.05.17 | PARRTJIMA 2.0

Advertising