Barks Bigger than Ben Hur

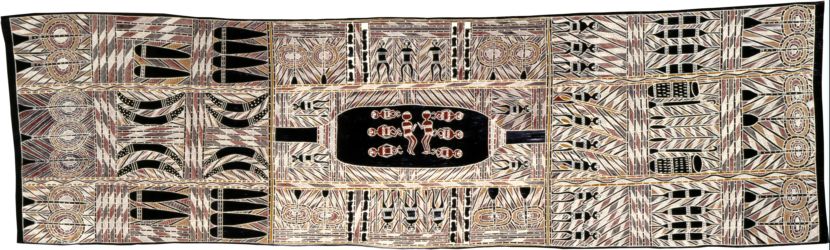

The amazingly complex work by Narritjin Maymuru, 'Resume of His Subjects', (1965), 45.7cms x 73.66cms. © 2017 the artist courtesy Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre, Yirrkala.

Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 05.06.17

Gallery: Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection

The bark paintings of Australia's Aboriginal North, so easily put into the shade by the brilliant acrylics of the Deserts, are coming out into the sun. As a foretaste, the Queensland Art Gallery is bringing out Masterworks from the Janet Holmes a Court Collection in July – who knew that the Holmes a Courts had been tucking away barks in the 80s and 90s? And of course, the great Makarrata – not the suggested Recognition one, but one sealed with ceremony last year on the island of Milingimbi – is intended to bring out a stream of historic art from that Yolngu community, though the excellent debut show at the Art Gallery of NSW was on for far too short a time over Christmas.

And then, in 2019, we'll see a foretaste in Australia of what will be the biggest bark exhibition the US has ever seen – collecting together historical works going back 70 years, works commissioned in the 1990s and the work that's being done today. “Taken together”, says the press release from America's Kluge/Ruhe Museum, “they will show how Aboriginal art has changed – and remained the same”.

It goes on, “The Kluge-Ruhe is the only museum in the U.S. dedicated to the exhibition and study of Aboriginal art, providing University of Virginia students unique access to what would otherwise be a faraway community. It was established in 1997 when the late businessman John W. Kluge entrusted UVA with his collection of Aboriginal art, including the collection and archives of Ed(ward L) Ruhe, who helped bring Aboriginal art - especially its barks - to America”.

Far from existing only for Americans, the Kluge has a regular flow of Aboriginal artists to fertilise the art on the walls – and in storage. In 2015, for instance, Djambawa Marawili from Yilpara in NE Arnhemland was in residence. His challenging conclusion - “We need to get this out of the drawers, and do some new work to update your collection”. He was particularly referring to the 1996 commission of 29 works from the Buku Larrnggay Mulka art centre in Yirrkala. Specifically, at that time, Kluge was interested in Yolngu bark paintings containing sacred designs painted on long, thin panels of eucalyptus bark.

“It was a major moment for that art centre”, explains the newly appointed curator at Kluge, the Australian Henry Skerritt, “because bark painting had somewhat fallen out of fashion by the 1980s. With John Kluge’s commission, the Yolngu artists were able to produce work at the kind of scale that had not been seen for decades.” Soon afterwards, off their own bat, they produced the monumental 'Saltwater' suite of barks to assist an ultimately successful sea right legal claim.

The other key facilitator in the increasingly complex project is former Buku worker, Kade McDonald. It was he who backgrounded the process for me – involving the University of Virginia, art from the Smithsonian Museum, a new commission of 30 works from current artists at Buku, some of whom were part of the 1996 commission and are still working, and the efforts of a younger generation at Buku who make films as often as they paint barks. These films will record the making of the new art, but will also go as far as possible to introduce the American audience to the culture and lore that continues to rule Yolngu life today and is the context for the art-making.

As part of this “bigger than Ben Hur” process, McDonald was recently in the US with Buku Chairman Yinimala Gumana and artist Wukun Wanambi to begin the process of selecting the historical artworks to give expression to the title of the project, Madayin. Madayin (sometimes Mardayin) are the geometric designs, miny'tji, on barks that represent the 'inside' world of the ancestral past for Yolngu, extended it into the present through the act of painting. The 'outside' world which non-Yolngu can share in greater detail comes in the form of figurative characters from everyday life.

A work like Narritjin Mayamru's 'Resume of His Subjects' from 1965 in the Kluge/Ruuhe Collection, is an amazingly complex congregation of the artist's world view. Ancestral figures and the anvil-shaped thundercloud that represents death, various totemic animals and plenty of fish! The fish that lie within the elliptical shapes that are the yingapungapu, symbolise the body of the deceased which are placed upon that mortuary sand sculpture, and any maggots or sand crabs spotted feeding off the remains of the fish are actually an act of cleansing that looks towards renewal of that life in the future.

“I am here to discover the Madayin of my ancestors so that I know it is here, safe,” Wukun Wanambi explained. “It is for us, the Yolngu, to understand that it is here in another world. The exhibition will be held here in America to show the Madayin, to show the strength of our art on bark, from the past to the present, and as it continues, passed on from generation to generation.”

The Maymaru bark was collected by Ed Ruhe when he came for a year as a Fulbright Scholar to Adelaide University in 1965. In those pre-acrylic days, he fell for bark art and spent much time in Arnhemland communities such as Milingimbi, and buying the important Spence Collection containing works as early as 1948 when no Australian institution took the slightest interest. Like UVA, he later brought artists to his Kansas U, and made sure he had the appropriate background information with every artwork. John Kluge bought the Ruhe Collection after his death.

McDonald and the two Yolngu artists toured beyond Virginia recently in an effort to arouse “US ownership” of the project. In part, this involves raising a million dollars to fund the 30 new commissions – perhaps linking individual philanthropists with individual artists – and in part this means wooing the institutions that will host what they are claiming as the first historic survey of Aboriginal bark paintings ever staged outside Australia. “They will all be contemporary art venues, not anthropological museums”, Kade McDonald stresses.

“These kinds of experiences are so important for our students, because they really broaden their understanding of the world,” the Kluge-Ruhe's Director, Margo Smith said. “We are always looking for ways to connect these artists – who are the best experts on their work and how we teach it – with students across all disciplines.”

While Australia will see the new works in 2019, the American tour starts in 2020 and may run for a couple of years.

URL: http://www.kluge-ruhe.org

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

Gallery: Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection

Contact: Margo Smith

Email: kluge-ruhe@virginia.edu

Telephone: 434 244 0234

Address: 400 Worrell Drive Peter Jefferson Place Charlottesville Charlottesville 22911 Va

Gallery: Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection

Contact: Margo Smith

Email: kluge-ruhe@virginia.edu

Telephone: 434 244 0234

Address: 400 Worrell Drive Peter Jefferson Place Charlottesville Charlottesville 22911 Va

Buku Larrnggay Chairman Yinimala Gumana examines a bark in the Kluge/Ruhe Collection with Kade McDonald

Yalmay Marika, 'Wagilag Dhawu' (The Creation Story of the Wagilag Sisters), part of the 1996 commission by John Kluge. 260cms x 75cms. © 2017 the artist courtesy Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre, Yirrkala.

Where is the exhibition?

Further Research

Gallery: Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection

Artists: Djambawa Marawili | Narritjin Mayamru | Wukun Wanambi | Yalmay Marika | Yinimala Gumana

News Tags: Buku Larrnggay Mulka art centre | Henry Skerritt | Janet Holmes a Court Collection | Jeremy Eccles | Kade McDonald | Kluge/Ruhe Collection | Margo Smith | Milingimbi Makarrata | University of Virgina

News Categories: Australia | Blog | Event | Exhibition | Feature | Industry | News | North America | Other Event

Exhibition Archive

- 10.10.17 | TARNANTHI 2017

- 11.08.17 | Natsiaas 2017

- 20.07.17 | APY ART DOMINATES THE WYNNE

- 17.07.17 | Anangu Artist Wins $100,000 Prize

- 14.07.17 | The End of AAMU

- 11.07.17 | ART ACROSS THE COUNTRY

- 11.07.17 | TARNANTHI IN OCTOBER

- 05.07.17 | TJUNGUṈUTJA - from having come together

- 13.06.17 | Ghost-Nets Straddle the World

- 07.06.17 | Grayson Perry Going Indigenous?

- 05.06.17 | Barks Bigger than Ben Hur

- 27.05.17 | NGA QUINQUENNIAL 2017

- 21.05.17 | Blak Douglas Finds Home at the NGA

- 21.05.17 | BRIAN ROBINSON WINS HAZELHURST WOP

- 18.05.17 | PARRTJIMA 2.0

Advertising