A TRIBAL WORLD ON VIEW

Amazing image of a Kazakh Eagle Hunter in Mongolia by David Edwards

Jeremy Eccles | 13.03.10

Author: Jeremy Eccles

I was drawn to this gorgeous and important book, 'We Are One' by the prospect of Damien Hirst – the English artist infamous for his crazy concepts like a floating shark or a diamond encrusted skull – sharing his views on Aboriginal art! Unlike his art, though, his words actually make sense:

“Aboriginal artists say that it is difficult to find any Aboriginal art that is devoid of spiritual meaning. Art is their culture, their work, their worship, their history. A painting is a chronicle of their country, a map of myths, a memoir of the great spirit ancestors of the Dreamtime. And their paintings are inextricably woven with their love of the land; they are 'dancing, singing and painting for the land'.”

And that, says Jo Eade of Survival International, which produced the book, puts Australian Aborigines on a par with the 370 million indigenous people around the world – especially the 150 million defined as 'tribal' who are separate, remote and in danger of losing everything that gives their life meaning; all connected together by the centrality of land to their lives and by persecution from the dominant majority.

'We Are One' – compiled from some of the world's most poignant and beautiful photographs and moving texts by a mix of indigenous thinkers and Western observers – is the product of an organisation that's not well-known in Australia, Survival International. That came into being in 1969 in fear of a total wipeout of Brazilian Indian tribes in the Amazon forests. And it retains the priority of publicising and campaigning against threats to South and North American and Asian indigines, such as, currently, the plans by Vedanta Resources to dig up a mountain of bauxite in India that's sacred to the Dongria Kondh people.

It strikes me that it's a lot easier to take on such a clear-cut cause as that than it is to tackle the Northern Territory Intervention, even though it's making many of the same mistakes as those identified by Englishman Alan Campbell, in talking about Brazilian Indians: “The notion of 'integration' is such a lie. Indians are being invited to to give up their material, social, cultural, imaginative and emotional independence and join in the margins of a vast society, capitalist and consumerist, that sees no alternative to the immiseration of millions of its people in urban and rural poverty. Take away the Indians' land, their settlement patterns, their hunting areas, their gardens, their kinship network, their dances, their myths, and offer them....television and football, and a miserable shack on the side of the road. What a lie”.

That appears in the chapter on Exile – which actually opens with the root cause of so many Australian problems, the concept of 'Terra Nullius'. But Ms Eade is a lot more positive when dealing with such matters as Land, Wisdom, Celebration and Shamans – emphasising, amongst other things, that we're talking about peoples who still see their laws as coming from the gods rather than Man; and revealing the Colombian Indian belief that their creator, Kaku Serankua created four kinds of people – the white, yellow, red and black; also the colours of the four mantles of the earth. No surprise really that those are also the four basic ochres in Aboriginal ceremony and art.

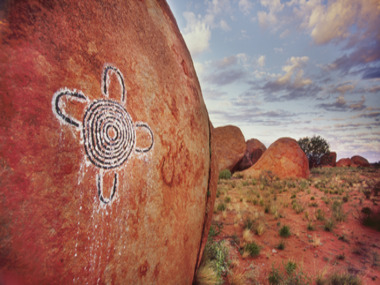

There's a fine text from Arnhemland's Wandjuk Marika about the importance of painting. But, sadly, only a single, odd contemporary Pintupi motif on a desert rock to illuminate the subject. It's a particular pity because it strikes me that the importance of art to the cultural survival of Aborigines in remote Australia may be their unique contribution to this international survey. By comparison with the others, Aborigines seem to come up short on ceremony, shamans and wonderful soul-bites like Sitting Bull's: “I am a red man. If the Great Spirit had wanted me to be a white man, he would have made me so in the first place. It is not necessary for eagles to be crows”.

And, as his fellow Sioux, Luther Standing Bear so wisely observes: “Only to the white man was Nature a 'wilderness', and only to him was it 'infested' with 'wild' animals and 'savage' people” - both of whom he needed to tame!"

Since this text is accompanied by a stunning image (copyright donated by photographer David Edwards) of the Grand Canyon in a swirl of misty pink clouds that could coexist in a Rammey Ramsey painting, one can clearly see that the tribal links across the Continents are all there.

The book - 'We Are One' is distributed in Australia by Hardie Brant Books of Melbourne at $75.

URL: http://www.hardiegrant.com.au/Books/Books/Book.aspx?isbn=9781844007295

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

Pintupi Rock Painting from an unknown site in Central Australia, photographed by Frans Lanting

Further Research

Artists: Damien Hirst | Rammey Ramsey | Wandjuk Marika

News Tags: Damien Hirst | Survival International | Vedanta Resources

News Categories: Book

News Archive

- 11.10.17 | RETURN OF MUNGO MAN

- 10.10.17 | TARNANTHI 2017

- 11.08.17 | Natsiaas 2017

- 08.08.17 | ABORIGINAL ART ECONOMICS

- 02.08.17 | SCHOLL'S NEXT MOVE

- 20.07.17 | APY ART DOMINATES THE WYNNE

- 17.07.17 | Anangu Artist Wins $100,000 Prize

- 14.07.17 | The End of AAMU

- 13.07.17 | YOU ARE HERE

- 11.07.17 | ART ACROSS THE COUNTRY

- 11.07.17 | TARNANTHI IN OCTOBER

- 05.07.17 | TJUNGUṈUTJA - from having come together

- 02.07.17 | BENNELONG

- 27.06.17 | JIMMY CHI

- 23.06.17 | Blak Markets at Barangaroo

Advertising