'HALF WAY BETWEEN ROTHKO AND POLLOCK'

Pat Corrigan proudly holds his new book in front of one of its subject's canvases during the book launch at Australian Galleries in Sydney

Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 05.05.15

The enthusiasm of businessman and art collector Pat Corrigan is undiminished at 82. Having made a motza out of freight forwarding, this nugget of a man has embraced art for 40 years, accumulating 3000 works, 1000 of which have been donated to 45 institutions – galleries, universities, etc so that the widest possible public can experience them. Since 2003, he's added Aboriginal art to his portfolio – leaping into the then-newly happening APY art scene and finding other artists who matched its vibrancy. Three large format books have resulted as he shares that vision widely as well.

The latest is devoted to Mirddingkingathi Juwarnda Kabaratjingathi – far better known as Sally Gabori. No fewer than 108 works of her's have joined the Corrigan Collection since 2006 – almost an addiction, one might say! I've seen only a few in the flesh – but all in the book – and they do reflect Corrigan's taste for the most challenging of colour combinations. I note, by comparison that the NGA's last Triennial featured Sally in 2012 – I seem to recall that the lady danced and sang her works on to the walls – and their selected trinity contained just three colours – red, black and white. You can find seven, including an eyeball searing green, in a Corrigan.

I have to say I prefer the more restrained Gaboris. But it is suggested that Mornington Island Arts, her art centre, sent most of these off to the Alcaston Gallery in Melbourne, which is credited in the Corrigan book with having “supported the artist over many years (and) helped to achieve her international acclaim”.

Of course, all of her works speak through Gabori's memory of the land and sea. These include important water sources on the tiny Bentinck Island at the bottom end of the Gulf of Carpentaria that somehow managed to support its Kaiadilt people for thousands of years in virtual isolation from the rest of the world, black and white; good fishing spots off-shore; the extensive man-made fish-traps that meant that the animal side of their diet was often simply delivered to them; places of ancestral legend such as Dibirdibi, where the Rock Cod sacrificed his liver to be thrown on to rocks to create a perpetual spring; right down to tiny patches of coloured rock exposed by certain tides that reminded the Kaiadilt of the scales of the Rainbow Serpent.

But how was it that Sally Gabori interpreted this range of subjects so non-specifically in mighty abstract patches of colour that Daniel Rosendhal's photos of Bentinck in the book reveal must have been unseen and unimaginable in her formative years?

It's important here to realise that the Kaiadilt had been living on the neighbouring Mornington Island for 57 years when Sally started to paint. Their isolation and their paganism (including polygamy) had been a constant challenge to the Presbyterian missionaries on Mornington, who, in 1948, seized on the coincidence of a multi-year drought, an extraordinary tidal surge that covered the island for most of a day and inter-dolnoro (family groups) fighting that had reduced the tribe's population to just 42 on Bentinck, to forcibly transport them to Mornington.

There they joined other Kaiadilt who'd variously left of their own accord and those who'd been exiled to Aurukun on Cape York to make a tribe of 83, according to the 1962 study by ethnologist Norman Tindale from the South Australian Museum. He lists Sally amongst the 42. Oddly, the Corrigan book says 63 were removed, which may be the legend today. But its authors Djon Mundine and Candida Baker seem unaware of Tindale's almost contemporary study. In 1942, there had been a peak 20th Century population of 123.

An extraordinary 'lost tribe' story – a world in which learning the significant places and food sources on Bentinck was an essential aspect of survival for what Kaiadild linguist Dr Nicholas Evans evocatively calls 'The People of the Strand'. Djon Mundine calls Gabori's paintings “a memory world” and a “mnemonic jingle” for a people who had no visual art tradition whatsoever.

But I wonder whether, after two thirds of her life away, Sally was actually thinking like an abstract expressionist artist when she evoked her distant memories of subjects by the size of their importance – steadily becoming less-detailed as she developed as an artist. After all, Corrigan himself described her as “Half way between Rothko and Pollock”, in an ABC Radio interview.

Far more important, and sadly missing from the book, is the link identified by Dr Evans between language and art. In a moving commentary, Evans states, “Such was the trauma of this forced shift (to Mornington Island) that for several years no child was born and survived, rupturing forever the chain by which one sibling transmits language to the next”. This tragedy meant that Sally could never pass her tribal lore on to the many offspring of her own children through song or conversation. Painting was the only way.

And painting has paid for Gabori's return to establish an outstation on Bentinck Island. At a rate of a canvas a day, Mundine suggests that there are literally thousands of her paintings out there – which either reflects the market's hunger for this unique Aboriginal art voice, or raises a question about the commercial nouse of Mornington Island Arts in allowing the 81 to 91 year old artist to tell her tale so enthusiastically and so often.

But, as Mundine colourfully puts it, “She brought a visceral, heartfelt energy to her paintings”. Baker adds words like “volcano” and “the molten lava of her searing palette of colours and shapes”. Simon Turner, who first showed Gabori at the Woolloongabba Gallery in Brisbane saw in those shapes the mighty clouds that build in the tropics, such as the notorious Morning Glory formation that can be hundreds of kilometres long and is today used by trippers for cloud-surfing.

My favourite new understanding from the book is the revelation by Candida Baker that, despite the polygamy which saw a man have up to 17 wives, and which also saw young men tempted to kill their elders when the supply of potential wives ran out, the Kaiadilt was amongst the most gender-equal in Aboriginal Australia.

Thank you Sally Gabori for drawing the world's attention to this culture. And thank you Pat Corrigan for promoting that culture in this tome from Macmillan available online at a cost, delivered of $99.

URL: http://www.palgravemacmillan.com.au/palgrave/onix/isbn/9781922252098

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

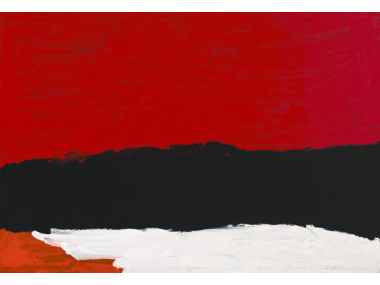

'Dibirdibi Country' (2009) - Sally Gabori tells the heroic legend of the Rock Cod in restrained style

'Dibirdibi Country' (2012) - the later Sally Gabori expands her colour palette

Further Research

Artists: Sally Gabori

News Tags: Bentinck Island | Candida Baker | Djon Mundine | Greg Weight | Jeremy Eccles | Kaiadilt | Mornington Island | Pat Corrigan | Sally Gabori

News Categories: Book | Event | Feature | Industry | News | Other Event

Exhibition Archive

- 10.10.17 | TARNANTHI 2017

- 11.08.17 | Natsiaas 2017

- 20.07.17 | APY ART DOMINATES THE WYNNE

- 17.07.17 | Anangu Artist Wins $100,000 Prize

- 14.07.17 | The End of AAMU

- 11.07.17 | ART ACROSS THE COUNTRY

- 11.07.17 | TARNANTHI IN OCTOBER

- 05.07.17 | TJUNGUṈUTJA - from having come together

- 13.06.17 | Ghost-Nets Straddle the World

- 07.06.17 | Grayson Perry Going Indigenous?

- 05.06.17 | Barks Bigger than Ben Hur

- 27.05.17 | NGA QUINQUENNIAL 2017

- 21.05.17 | Blak Douglas Finds Home at the NGA

- 21.05.17 | BRIAN ROBINSON WINS HAZELHURST WOP

- 18.05.17 | PARRTJIMA 2.0

Advertising