Aboriginal Art is “An Exceptional Art Form”

The book (from Routledge) from which this article was extracted

Jeremy Eccles | 26.08.20

Author: Prof Tony Bennett (ital), with comments by Jeremy Eccles

News source: The Conversation

Many Australians are sharply divided as to whether they prefer more traditional genres of art like landscapes or more contemporary and abstract visual forms. And these divisions relate to differences in age, class and education. But Aboriginal art bucks this trend because it is seen as “telling a story”.

New analysis by Prof Tony Bennett at the Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University, working with fellow academics and writing in The Conversation, shows landscape art is the most popular visual art genre among Australians, with Aboriginal art coming in second place, followed by portraits and modern art.

But Aboriginal art is more likely to bridge social divides and can dissolve personal prejudices between different kinds of art.

The research is discussed in a new book called Fields, Capitals, Habitus: Australian Culture, Social Divisions and Inequalities published by Routledge.

Researchers conducted a national survey of Australians’ cultural tastes, doing surveys with 1,202 Australians. Extra samples to ensure representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Italian, Lebanese, Chinese, and Indian Australians, brought the overall survey total to 1,461.

Aboriginal art was the second most popular genre, liked by 26% of the main sample, behind landscapes (52%) but ahead of portraits (24%) and modern art (17%). Impressionism and Renaissance art came in at around 15% each, while abstract art, colonial art, Pop art and still life's ranged, in order, from 13% down to 7%.

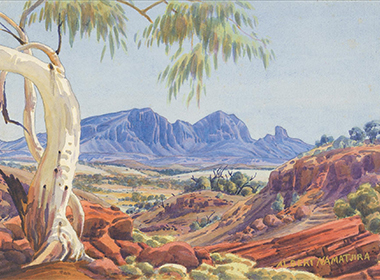

Survey respondents were given a selection of artists and asked to say whether they had heard of and liked them. Indigenous landscape painter Albert Namatjira was the third most familiar but, at 63%, he was only narrowly pipped by painter Sidney Nolan (67%) and the colourful Ken Done (68%). Indigenous multi-media artist Tracey Moffatt was less well known (14%). But, in the popularity stakes, Namatjira was the most popular of all, liked by 49% ahead of both Nolan (42%) and Done (40%).

Unsurprisingly, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were much more enthusiastic about Aboriginal art (67%) and Namatjira (liked by 70%) than the main sample, but not notably so for Moffatt. Indian and Lebanese Australians also showed a marked liking for Aboriginal art at 38% and 36% respectively.

Aboriginal art also had a broader cross-class appeal than most genres. It did, however, appeal more strongly to those in the middle-classes (such as self-employed and clerical workers) and professional and managerial occupations than to those in skilled or unskilled working-class occupations.

Namatjira was most popular with the older members of Australia’s intermediate classes. Moffatt, by contrast, appealed most to the younger, tertiary-educated Australians in professional and managerial occupations.

There were clear correlations between these preferences for particular Indigenous artists and genre tastes. Those who liked Namatjira preferred traditional and largely figurative genres – landscapes, still lifes, and portraits. Those who liked Moffatt favoured genres tending towards abstraction or critical engagements with figurative conventions – modern art, Pop art and abstract art.

A key finding of the research was how much those who liked traditional and figurative genres disliked contemporary and abstract genres. The reverse was even more true: those who liked contemporary and abstract art often had a strong aversion to traditional and figurative art.

Yet the category of Aboriginal art often crossed the boundaries between these two groups of genres.

This is not entirely surprising. Aboriginal art has expanded beyond its traditional forms to include acrylic dot art, contemporary urban Aboriginal art practices, rock art, or the kitsch forms of “Aboriginalia” like that collected by Tony Albert.

But what is surprising is how frequently, when discussing their art tastes in follow-up interviews, survey respondents treated Aboriginal art as an exceptional art form. While most viewed it as a form of abstraction, it was seen as a purposeful abstraction with a story to tell, crossing the boundaries between the abstract and the figurative.

It was on these grounds that Aboriginal art was let off the hook by those who usually disliked non-figurative art. This was pithily summarised by one respondent who, dismissing modern and abstract art as “equivalent to what my daughters would do in kindergarten”, praised the “uniqueness of Aboriginal art and the dots” because “there’s stories behind it – there is the story they are trying to tell”.

This was a recurring theme in appreciations of Namatjira. In a follow-up interview, one survey respondent – a professional in a high-level executive role – liked Namatjira's work for not being “too abstract” in its depiction of “the beauty of the bush and the country”.

For another, a part-time accountant and labourer, Namatjira served as a counter to his dislike of modern and abstract art because his paintings are “real … they just feel like he's telling a story in his pictures and they're real”.

And a third, a woman in her 30s from a Sri Lankan background, expressed her appreciation of Namatjira and Moffatt in similar terms. She loved “Tracey's storytelling with its strong style and voice”, emphasising its appeal to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women while singling out the “cultural connections” that Namatjira's work makes.

While different kinds of Aboriginal art appeal to different publics, the category of Aboriginal art is one that recruits a broader interest. The academics got a strong sense that it is something that non-Indigenous Australians felt they ought to like and know more about because of what it has to say about Indigenous culture, its relations to Country, and its significance for Australian culture and identity.

This registers a significant shift from the terms in which Namatjira was initially appreciated, in the 1950s, as an imitative adaptation of pastoral modernism (Jeremy Eccles - by whitefellas!).

It is a shift that appreciates the work of Indigenous artists, curators and critics in stressing the role that Aboriginal art can play in transforming the relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

From Jeremy Eccles:

What conclusions can one draw from Prof Bennett et al's work? Of course, AAD readers will know many of its conclusions already - that First Nations art (much of which is landscape and keeps winning the Wynne Prize) is an essential way for its creators to share their culture with non-Indigenous viewers, has a spiritual and social purpose, crosses age, class and taste boundaries, and, had Emily Kngwarreye's name been on the academics' lists, she might have topped the old Albert in popularity.

Will the Art Gallery of NSW drop the Archibald for a First Nations art prize? Will it encourage States other than South Australia to consider an institution to popularise and explain the complexity behind the art? Will the gulf between the classical and the urban in Aboriginal art exposed by the numbers encourage a separation of the two distantly related forms?

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

Albert Namatjira's 'Hermannsburg' (c1951) created at the height of his early popularity

The 14%-known Tracey Moffatt – unfair for a Venice Biennale star and the creator of this ironically entitled image, 'Picturesque Cherbourg'

Further Research

Artists: Albert Namatjira | Emily Kngwarreye | Tony Albert | Tracey Moffatt

News Tags: Archibald Prize | Institute for Culture and Society | Jeremy Eccles | Ken Done | Prof Tony Bennett | Western Sydney University | Wynne Prize

News Archive

- 02.09.20 | Consulting the Industry

- 27.08.20 | Goodies from Canberra

- 26.08.20 | Aboriginal Art is “An Exceptional Art Form”

- 25.08.20 | Tarnanthi 2020

- 24.08.20 | Art Fairs Exit - and Entrance

- 12.08.20 | Fairs Fare

- 07.08.20 | “The Art of the Nation”

- 06.08.20 | Art Is Fashionable

- 06.08.20 | The Salon, 2020

- 03.08.20 | MR R PETERS 1935-2020

- 30.07.20 | EMILY v DOROTHY

- 27.07.20 | The Convict Valley – The Hunter

- 15.07.20 | Repatriated Art at Auction

- 08.07.20 | Kaurna Shield Comes to Adelaide

- 02.07.20 | Yiribana

Advertising