CANBERRA

'Adhaz Parw Ngoedhe Buk/Frigate Bird Mask' (2008) by the Torres Strait master, Alick Tipoti, at the NGA

Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 28.04.21

Gallery: National Gallery of Australia

There are fascinating differences between the two major institutions in Canberra in the presentation of their First Nations collections. At the National Gallery you can't avoid the Indigenous even as you hurry in to make your timed booking for the Big Show, 'Botticelli to van Gogh'. The increasingly sacred 'Aboriginal Memorial' of 200 silent lorrkon haunts the entrance; the First Nations galleries are beside you as you ride up the escalators; and ahead, in the main building, the new 'Belonging' juxtaposes black and white images of the country. Even the big 'Know My Name' showing of women's art closes – or maybe opens - with the contribution of Aboriginal women.

And there's still the fourth Indigenous Triennial – actually another Quinquennial – to come in November.

Meanwhile, over the Lake, the National Museum seems to want you to work extra hard just to find their First Nations galleries. Up and down stairs or a lift, outside and inside the building, un-signposted and then disorderly. Why would you place the currently trendy show of Indigenous fashion, 'Piinpi' in the middle of a historic display, I wonder? I'm reminded that the Art Gallery of NSW traditionally kept the Indigenous in its basement, though it is promising to do an NGA when 'Sydney Modern' opens: “Facing our original building across an art garden, the expansion is due for completion in 2022 and will place historic and contemporary works by First Nations artists front and centre”, promises Director Michael Brand in 'The Art Newspaper'.

Of course, most NGA visitors will currently be heading for those 'Sunflowers' in the UK National Gallery's grand touring show. Plenty else to delight, mind you - Rembrandt's self-portrait, Turner's sunset, Monet's waterlilies, El Greco's Christ, and an insightful portrait of the Russian-born man who kicked off the Gallery's collection. But see if you can spot a wild horsewoman in a British hunting scene. Glorious stuff. It's on until 14th June and, in my experience, the timed ticketing makes viewing a delight – rarely a crowd, even in front of those glowing sunflowers.

The many specialist First Nations galleries at the NGA used to be themed. A couple have hung in, but they seem to have given up on trying prior to a major re-hang next year as part of the NGA's 40th anniversary. It's a jumble currently – and, compared to the British show and the Women's, there's a sense that no one's even bothering in the explanation stakes. A wall of Ngkurr paintings – delightfully varied in style, probably differing by language group affiliation – are totally unlinked. Two Emily Kngwarreye's from different periods are hung in different rooms. A timely Easter painting from Milingimbi is unrelated to either a trio of delightful carvings from there or a Hector Jandany 'Ascension'. Daniel Walbidi is hung apart from the Yulparija ladies with whom his art is inextricably linked.

But there are treasures amongst the jumble. A Jack Keradada 'Wandjina' is the finest I've seen from that family. And two of the remaining themed rooms have treasures – a rusting tin mask by Alick Tipoti is really special; and an unusual seasonal Namatjira (Albert) stands out in the gloom of the Hermannsburg water-colour room.

'Know My Name' is a rich selection of Australian woman's art – and it's only Part 1! But the First Nations choices seem selected by size – big size, which is a much more widespread problem as architects throw up contemporary galleries by the metre rather than relating them to the wall-spaces of houses for which so much art was actually intended. Sadly, as a result the centre-piece commission of Tjanpi figures telling the 'Seven Sisters Story' loses much of the quirkiness that the flying version delighted with in Margo Neale's trend-setting National Museum exhibition – now in Perth. They're just big – and how many people are going to link the harried sisters with their priapic male pursuer peeping out from behind a tree in the corner?

Finally at the NGA, their corridor show 'Belonging: Stories of Australian Art' is described as a “major collection presentation recasting the story of nineteenth-century Australian art. Informed by the many voices of Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures and communities, the display reconsiders Australia’s history of colonisation”.

I'm not sure it can really claim such an impressive result, but it certainly contrasts the colonial vision of lush country, increasingly populated by sheep and cows but absent of its First Peoples; missing its YawkYawk spirits found in Kunwinjku Country; and denying its understanding of the seasons found in Shane Pickett's Nyoongar calendars. But then we could compare Augustus Earle's sympathetic Bungaree portrait and John Glover's charming Aboriginal cricketer with Ricky Maynard's adamantine 'Wik Elder' and Christian Thompson's sentimental self-portrait for points of difference (and similarity) in portraiture. Does Vernon Ah Kee's declarative text, 'We Grew Here' explain any of those differences?

By comparison, it's a single point of view at the National Museum – once you've found the First Nations galleries. The background material seems cogent; but Margo Neale's special exhibition, 'Talking Blak to History' is worth a challenging visit in its own right. She claims it shows that “Australian history didn't start in 1788; and Aboriginal history didn't stop then”. Well, apart from the wonderful Uta Uta Tjangala canvas, 'Yumari' (1981) with its multiplicity of ancient songlines criss-crossing Tjangala Country – a canvas rescued from the oblivion of being rolled up for 20 years in the NMA's stores – there's little to illuminate the first claim.

But the politics of survival are all around you. And it's presented by Aboriginal voices exclusively, via their political campaigning, in the suffering and grief of massacre and removal, in the prisons and the missions and then via the suicides, to taking control of their own health systems and even painting cars in traditional designs. Names involved include Gordon Syron, Queenie McKenzie, Michael Cook, Dick Roughsey, Lettie Scott, Fiona Foley, Vernon Ah Kee, Gordon Hookey, and Kevin Gilbert.

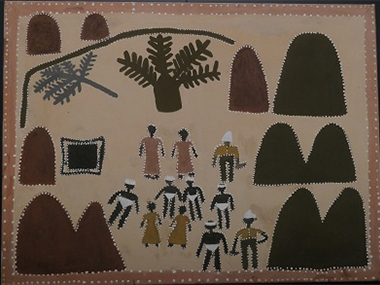

But the Museum's own politics also creep in. Another painting was denied a showing for many years – Queenie McKenzie's 'Mistake Creek' – the story of a notorious East Kimberley massacre of the Gija. Under a Howard Government-appointed board, this was considered 'Black Armband' history, to be denied. Now the massacre is accepted, but a cautious caption declares, “there is (still) debate about whether the killing party included any Europeans”!

Really?

URL: https://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/first-australians/talking-blak; https://nga.gov.au/belonging/

Share this:

»  del.icio.us

»

del.icio.us

»  Digg it

»

Digg it

»  reddit

»

reddit

»  Google

»

Google

»  StumbleUpon

»

StumbleUpon

»  Technorati

»

Technorati

»  Facebook

Facebook

Contact Details

Gallery: National Gallery of Australia

Contact: Franchesca Cubillo - Senior Curator Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art

Telephone: +61 2 6240 6502

Address: Parkes Place or GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 Parkes Parkes 2601 ACT

Gallery: National Museum of Australia

Email: information@nma.gov.au

Telephone: +61 2 6208 5000

Address: Lawson Crescent Acton Peninsula Canberra 2600 ACT

Jack Karedada's bark 'Wandjina' from about 1971 in the NGA's Indigenous galleries

Queenie McKenzie's controversial 'Mistake Creek' from 1997, only allowed to go on show at the National Museum this year

Where is the exhibition?

Further Research

Gallery: National Gallery of Australia

Artists: Albert Namatjira | Alick Tipoti | Christian Thompson | Daniel Walbidi | Dick Roughsey | Emily Kngwarreye | Fiona Foley | Gordon Hookey | Gordon Syron | Hector Jandany | Jack Keradada | Kevin Gilbert | Lettie Scott | Michael Cook | Queenie McKenzie | Ricky Maynard | Shane Pickett | Uta Uta Tjangala | Vernon Ah Kee

News Tags: Indigenous Triennial | Jeremy Eccles | Margo Neale | Michael Brand | National Gallery | National Museum | NGA | NMA | Tjanpi weavers | van Gogh

News Categories: Australia | Blog | Exhibition | Feature | Industry | News

Exhibition Archive

- 28.04.21 | CANBERRA

- 23.04.21 | Sydney Biennale - 'From a Brook to a River'

- 22.04.21 | 2021 Telstra NATSIAA Finalists Announced

- 29.03.21 | THE NATIONAL 2021

- 24.03.21 | All Revealed in Freo

- 22.03.21 | Bla Mela Kantri

- 19.03.21 | Two Big Moves

- 16.03.21 | The Very Late Charlie Flannigan

- 08.03.21 | PAPUNYA ART AT 50

- 19.02.21 | National Endowment for Indigenous Visual Arts

- 11.01.21 | "Lost in Another Person's Culture”

- 04.01.21 | Appreciating Mparntwe

- 09.12.20 | Museological Sydney

- 02.12.20 | Getting Back into the Habit in Sydney

- 25.11.20 | VICTORIA OPENS!

Advertising